Our child’s hearing loss journey from toddler to teen years

April 9, 2019

Watch: A Day in the Life of a Teen Musician with Hearing Loss

April 11, 2019The Architecture of Deafness

Through the architecture of deafness, we learn much about deafness itself.

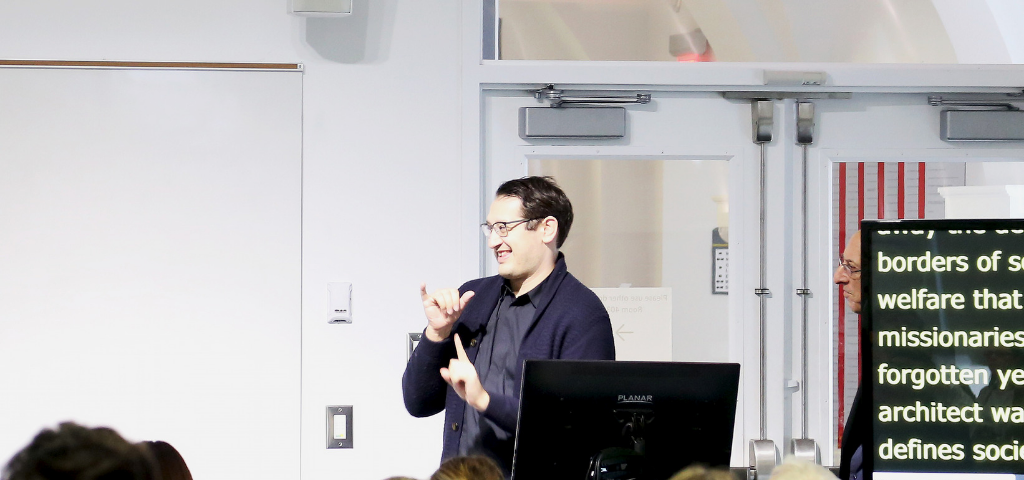

Jeffrey Mansfield, design director for Boston-based MASS Design Group, is one of a number of culturally Deaf designers practicing architecture. He presented on this topic at the Deafness and Architecture Symposium held at the University of Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning; this is the first article in a series reporting on this one-day event.

The Architecture of Deafness

Two years ago, Mansfield began a journey to visit deaf schools across the country. He wanted to understand how their architects formed a vocabulary around the social attitudes and approaches to the problem of deafness in America. He visited 150 schools, both current and discontinued, with diverse architecture. After the trip, Mansfield sought to develop a language for how to talk about the architecture of deafness, or what it means to be different in our society.

Sacred and Profane

The first theme he found is the interface between the sacred and the profane, the delicate balance between charity and control. In a broader context, the origin of the deaf school emerged from traditions of absolutism in the 18th century. The crown’s primary concern was the city’s appearance. The indigent was rounded up and sent to hospitals or charitable institutions located on the outskirts of the city.

The location of these particular buildings – often removed and set outside the city walls – goes back to the conception of the city itself. A boundary was enacted to prevent invaders and disease, usually in the form of a gate. People who were sick or ill hung out here hoping to collect from people entering the city. This edge of the city represented the medium of charity and control.

Aesthetics and the State

If you look at the design of state hospitals, deaf schools, universities, and prisons, you can see how the language of institutional architecture is similar. Aesthetics played an important role in demonstrating state power. Many schools were among the first institutions built by the state as the country expanded westward with the Indian removal act of the 1830s. Deaf schools and institutions became vehicles for the urbanization of the country. There was a sense of social virtue, pride, public confidence, and style to mark the presence of the state.

The Illinois School for the Deaf, for example, can accommodate over 200 students. Yet the building was erected in 1846 and only had nine students. “This begs the question, for whom was this school designed?” Mansfield asked.

Across America, many of these buildings were built in enormous scale at great cost to represent the best the state had to offer to those who were the least fortunate. As a result, the story of deaf schools is from the romanticized notion of America. With the first industrial revolution, the idea of schools provided a new solution. Schools would condition the indigent into a productive labor force, used for the benefit of society. The state-sponsored deaf school was part of this tradition.

Industry and Virtue

Agriculturalization became one way of offsetting the state’s cost while also providing long-term benefits of educating the deaf in habits of industry. This industrializing a cultural education became a hallmark of deaf schools. As society transitioned into a manufacturing society in the early 20thcentury, agriculture went out in deaf schools as well as an emphasis on physical fitness.

Power and Discipline

Unlike most schools, deaf schools had a direct trunk line to state actors that wielded power over their subjects. This played out in some very real and terrifying ways, Mansfield said. In many states, the deaf schools were placed under boards of control which also oversaw the state’s penitentiaries and hospitals for the insane. This resulted in confusion about what the state school was and what it did.

Last year, Mansfield visited the Oregon State School for the Deaf. When he entered the dorm, it was dimly lit. “It was obvious to me as I stood there that this was derived from a prison blueprint,” he said. “The space was identical to what we might see in a prison environment…It only had the bare minimum of design.”

Education and Pathology

The pairing of medicine and pathology was solidified in the 19th century through deaf education spaces. Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a physician who founded the precursor to the American Psychiatric Association, argued that a new type of architecture was needed to address issues of patient classification, effective supervision, limited budgets, and growth. He called for a phased approach for the state hospital, with wings separated by gender, the worst cases furthest away, and cafeterias and chapels located behind the main administrative core. These schemes were reproduced at the deaf schools, thus linking deafness and pathology through architecture.

Technocracy

In the 20th century, advances made it possible to improve the environment. Mechanical systems like central heating and cooling and elevators helped create indoor worlds. Education became more standardized.

Meanwhile, deaf schools were sites of the cultural resistance. The Wyoming School for the Deaf, built in 1963, was designed with sight as a central tenet. It has generous windows and skylights, and hollow core wooden floors that helped transmit vibrations.

A year ago, Mansfield visited a deaf school in Oslo, Norway, designed in 1975. The classrooms have circular arrangements. The building integrates into the landscape, maximizing multilevel sight lines, optimizing natural light and accommodating sign language with circular and semi-circular geometries.

“‘I felt as though I belonged,’ Mansfield said.”

“I felt natural. I felt learning was inclusive and meaningful although it occurs on the margin of society.” The deaf school is central to our understanding of it, he added. “Deafness does not need to exist in a bubble or vacuum,” he said.

What does this mean for our spaces? Mansfield asked. How can we design for inclusion? Inclusive design processes can promote well being as well as create educational and spatial justice, but Mansfield encouraged his audience to push further. “Can we also demand beauty?” he asked.

If you attended a deaf school, what was its architecture like?