5 ways restaurants can be more deaf-friendly

September 16, 2019

How to participate in Deaf Awareness Month 2019!

September 18, 2019Haben Girma: The story of a Deafblind trailblazer

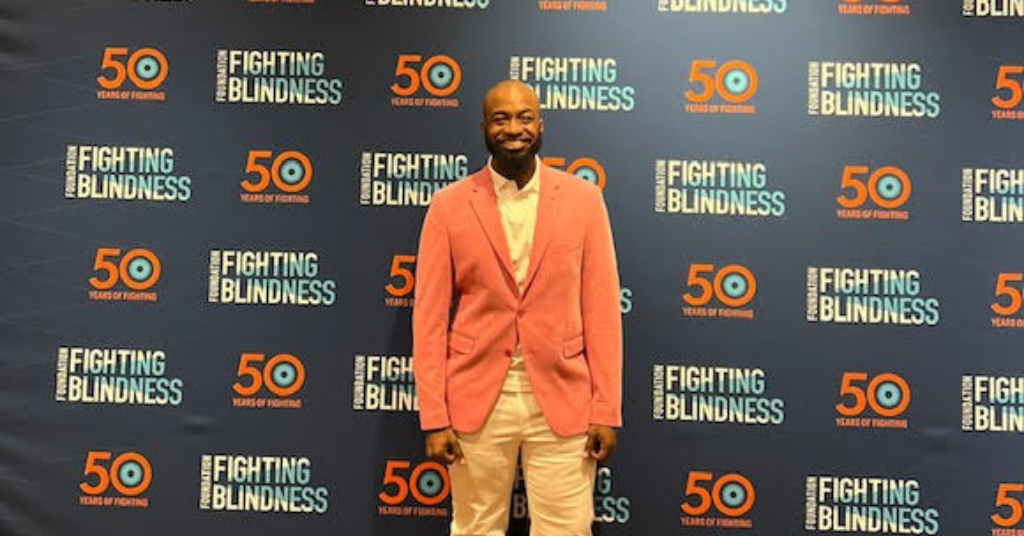

Photo credit: Office of Haben Girma

She has climbed icebergs in Alaska, used a radial arm saw, helped build a school in Mali, and faced a bull in Eritrea. All of this, despite being Deafblind. But don’t call Haben Girma inspiring.

As she tells People, “Some people use the word as a disguise for pity. ‘You’re so inspiring,’ they’ll say, but they’re thinking, ‘thank God I don’t have your problems.'”

The deafblind author

The latest achievement on Girma’s impressive list is the publication of her memoir, entitled “Haben” and subtitled “The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law,” which was released earlier this month. The 263-page book begins with a joke, which sets the tone. Her humor is evident throughout as she writes in the present tense, taking us through her life from childhood to the present day. In fact, she uses humor as a weapon to disarm disability-related awkwardness and create connections.

The 31-year-old says she doesn’t feel limited to being Deafblind. It’s all she’s known, so it’s her normal. And even that spectrum has changed. She used to be able to see indistinct outlines, but over the years, the images have faded. Her hearing has also worsened.

Early on, she’s aware of how unfair the world is. When describing a sighted, hearing classroom, in a sighted hearing school, in a sighted hearing society, she adds, “They designed this environment for people who can see and hear. In this environment, I’m disabled. They place the burden on me to step out of my world and reach into theirs.”

Positive Blindness Philosophy

At the Louisiana Center for the Blind (LCB) one summer before college, she learns a positive blindness philosophy to which those of us with hearing loss can relate. The director, Pam, talks about how the dominant culture promotes ableism, the idea that people with disabilities are inferior to the nondisabled.

“LCB teaches students to resist these ableist assumptions,” Girma writes. “After identifying and removing them, people can begin to lay the groundwork for a positive philosophy based on the idea that blindness is nothing more than a lack of sight.”

It’s here where Girma realizes her calling. When the director tells her students that she needs all of them to keep changing what it means to be blind, Girma vows to someday create a community of people who believe that disability isn’t a barrier. As she tells a college classmate, “Blindness is actually just a lack of sight. With the right tools and training, blind people can do just about anything. Like I travel, rock climb, and volunteer in my community. I just use alternative techniques.”

“With the right tools and training, blind people can do just about anything.”

Like any of us, Girma experiences ups and downs as she makes her way in the world. She learns how to advocate for herself and realizes that her efforts benefit others as well. She even figures out a better way to communicate when her hearing and vision worsen. It involves a keyboard and braille computer. When someone asks if it autocorrects, she brilliantly says, “I’m used to reading through typos, so my mind autocorrects.” How many times have we done this with captions?!

Fighting for Inclusion

After attending Harvard University, where she was the first Deafblind student, she’s on the legal team of a groundbreaking case about the ADA and virtual “places.” She visits the White House, where she introduces and meets President Obama and Vice President Joe Biden. Eventually, she realizes litigation isn’t for her. Now she has her own business of disability rights consulting, writing, and public speaking.

There’s even “A Brief Guide to Increasing Access for People with Disabilities” at the end of the book. In it, she addresses the reality that most people will need to seek accessibility solutions at some point, whether for a family member, colleague, or oneself.

“Disability is part of the human experience,” she writes. “We all need to engage in the work to make our world accessible to everyone. Inclusion is a choice.”

Haben Girma’s memoir brings this point home. If anything, it’s motivational, because we face similar challenges.

Read more: How I changed my attitude about hearing loss